Recruiting Toolbox Blog

Diversity. How did we get here? (Part I)

[This blog post first appeared on LinkedIn in June 2020]

For 76 Years, Corporate America has Failed to Hire Black People

On this day in 1944, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act. Commonly known as the GI Bill, it offered federal aid to help veterans buy homes, get jobs, and get college degrees.

By the time the bill expired in 1956, almost half of the 16 million World War II vets had received education or training through the GI Bill. U.S. college and university degrees doubled between 1940 and 1950.

The bill also provided home loan assistance. By 1955, the government granted 4.3 million home loans worth $33 billion to veterans.

With the boost of newly educated veterans with access to capital for home loans, the 1950s was a period of economic prosperity for Americans. Cheap oil, advances in science and technology, a growing consumer economy and infrastructure investment led to wage increases and a shift from blue collar labor to white collar jobs.

Unemployment dropped, and upward mobility increased. Property ownership and increasing wages contributed to comfortable lifestyles in growing suburbs. More families were able to afford to send their kids to college. By 1970, 70% of jobs in the U.S. were white-collar jobs.

The surplus of jobs meant that the barrier to entry was low. Companies hired college grads and provided on-the-job training. High performers were selected to climb the ladder and supported by management training programs. Often, a referral from a friend, neighbor or relative substituted for a college degree.

Hold up Carmen. You’re supposed be talking about diversity recruiting. Why the history lesson?

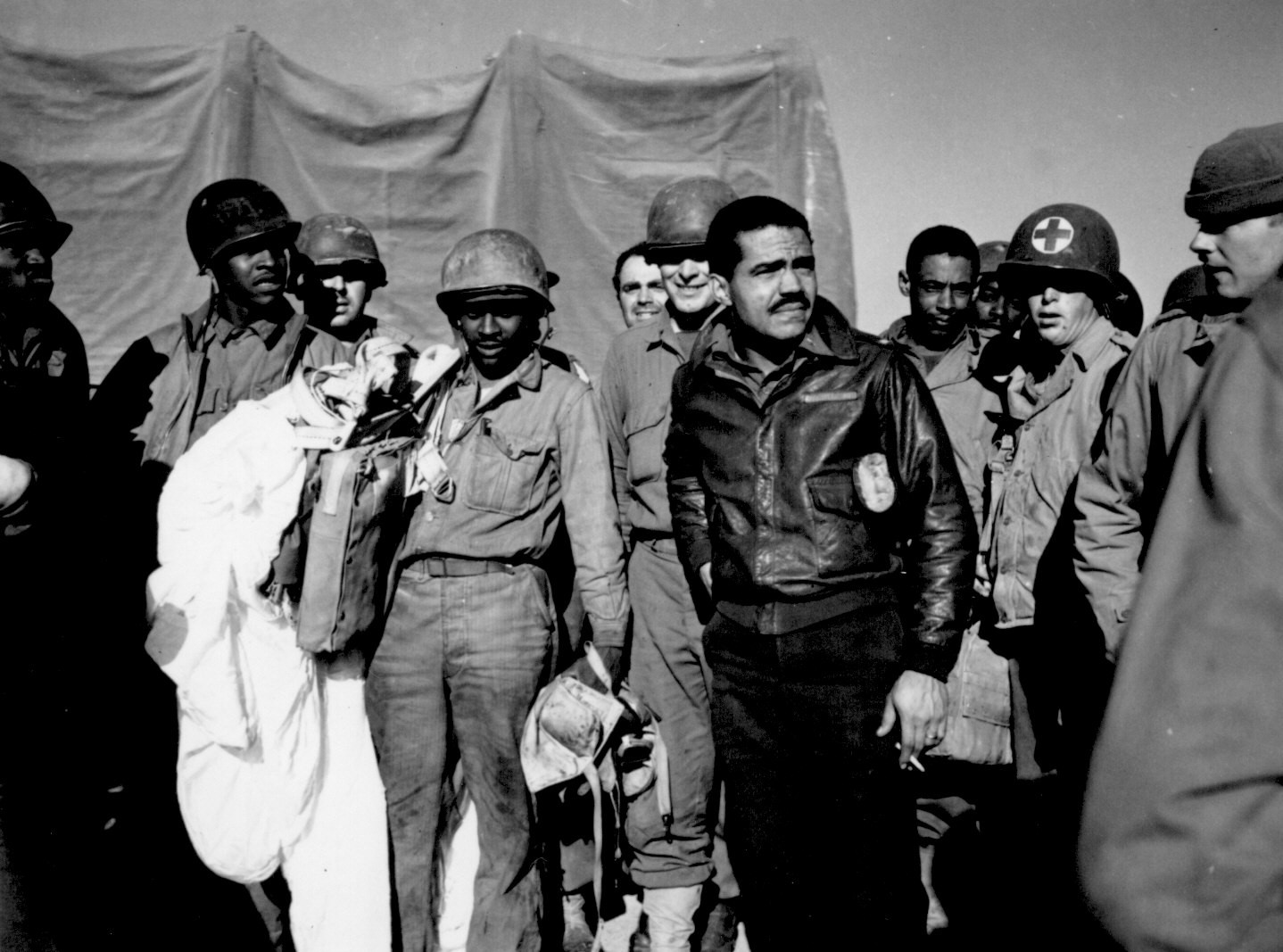

Because 1.2 million black men served in World War II, including my father. Largely, black Americans were excluded from the benefitting from the GI Bill through Jim Crow laws, discharge status or blatant discrimination and racially encoded practices like redlining.

(photo of 99th Fighter Squadron of Army Air Force courtesy of National Archives)

African Americans weren’t able to participate in the biggest economic boon of the 20th Century. Economic inequality didn’t start in the 1950s, but the wealth gap expanded significantly as a result.

Meanwhile, Corporate America grew, the white-collar workforce expanded, and discrimination against black people became an embedded – if not explicit – practice. White men hired other white men. Eventually white men hired white women. But racial stereotypes persisted.

Today, the professional workforce continues to be plagued by a lack of African American representation and a seemingly insurmountable wage gap.

I believe that in order to solve a problem – really solve it – you have to understand the genesis, the root cause. And the 1950s – the rise of white-collar employment that excluded black people – is foundational to the continued struggle to diversify the white-collar workforce.

But there are many people in Corporate America, many people among your ranks, who don’t understand, or don’t agree, that the root issue is discrimination. These are the people who are likely to voice (out loud or to themselves) questions like

- Don’t all lives matter?

- Do we have to hire less-qualified black people to achieve diversity?

- What about me? I’m not racist. Am I responsible for what’s happened in the past?

- What’s wrong with white people? Isn’t diversity – focusing on hiring based on race – reverse discrimination?

- I wasn’t privileged growing up. I made my own way. Why can’t we just hire the best person for the job?

- There isn’t a pipeline. How can we hire when there aren’t any black candidates?

And therein lies the challenge for organizations that are seriously committed to diversifying the workforce. A company must first admit and understand its complicity in discrimination if it wants to succeed at hiring and promoting more black people, and face, head-on, the tacit and explicit discrimination that is still taking place.

Without leadership that is ready to own that its' hiring, promotion and compensation practices – whether intentional or not – have served to deliberately exclude black people, diversity efforts are no more than lip service and are doomed to fail.

Once a company embraces its own discrimination, its leadership must take a public stance and embark on ensuring that its workforce deeply understands and is aligned with the pledge to increase diversity. This is difficult, because a significant portion -- perhaps most of -- your workforce is not aligned with diversity strategies. It is even more difficult when customers and partners are considered. Committing to an aggressive equity strategy may alienate employees, candidates, partners and customers.

Your company may have marshaled leadership support, and HR support, but many decisions are made in the middle. Hiring decisions, promotion decisions, decisions about who will get choice opportunities and important visibility are made by middle managers. Mostly white men. Many of whom are pondering the questions I listed above, feeling insecure, uncomfortable and even attacked. Many may harbor racial stereotypes.

Unless you make your expectations clear, and set consequences for resistance, it is likely your middle management layer will undermine your efforts to hire black people. This is why big tech companies, despite having poured effort and resources into hiring more underrepresented minorities, have failed to do so.

That’s how we got here. Discrimination and a deep-rooted belief in racial stereotypes. And this is where we are. Recruiting, hiring and promotion decisions that rely on risk-averse, racially biased, often unenlightened, and unaligned decision-makers.

Are you really ready to commit to a diverse workforce?

Part II – What Next?

I’ll talk about some tactical strategies that companies can implement to hire more black people. Preview: the strategies I suggest will not include bold statements, donations, or paying down student loan debt. Those things are nice, but they are not a proxy for equitable hiring, compensation and promotion practices.